Nick Hornby is one of my favourite authors. That’s mostly due to his 2005 novel A Long Way Down, which should be compulsory reading for everyone who’s ever considered suicide, even as the remotest of all possible possibilities. And his other books aren’t too shabby either. (With the exception of Fever Pitch, which is non-fiction anyway and of which I never managed to read more than two pages. Football… what more need I say?)

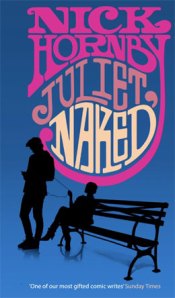

Now: Juliet, Naked.

The story revolves around three characters: Duncan, a teacher in his early forties obsessed with Tucker Crowe, an 80’s singer/songwriter; Annie, Duncan’s girlfriend of fifteen years; and finally Tucker Crowe himself, now no longer a musician but a recluse and father of five. Fairly in the beginning of the book we realize that Duncan knows more about Tucker than is good for him and that, mostly because of the Tucker issue, his relationship with Annie had a definite expiry date. I’m not spoiling much when I say that the two will break up fairly early in the book and that Annie will get to know Tucker Crowe. And that’s all I’ll say about the plot, for despite all the criticism that I’ll heap upon the book in just a minute, it’s still a very good book and you might do well to consider giving it a read.

Now. If Juliet, Naked is such a jolly good read, why do I speak of criticism?

For one thing, because of bad marketing. Just like Shyamalan’s The Village got sold as an all-out horror movie (which it isn’t), this book gets sold as … ehm… something that it is not. Okay, maybe I’m being a bit too hard on Hornby and the marketing department of Penguin/Viking here. I thought, from the jacket text, that the book would be about Tucker and Annie, not necessarily in a romantic sense, but in a talking-with-each-other sense. And it is, but only on the last hundred pages or so. Before that, it’s mostly either Annie or Duncan or Tucker sitting in a corner and being miserable. Erm… I’m being unfair again, they’re not miserable, which seems to me to imply postmodern yack about how incomprehensible and unfair the world is. The protagonists are sarcastic, doubtful, often witty as they wonder about their lives and where they would be today if things had gone a little differently for them.

This is not a bad thing, per se. If I could change only one thing about the book I would tone Annie’s incessant whining about her state of childlessness down a bit. That’s about it.

If I could change two things I’d have her meet Tucker sooner. Because Tucker is the most fun character in the book, but he needs a conversational counterpart to realise his true potential for awesomeness. The clashing of rock-star and museum curator, of British middle-class and American wash-out, that’s where the book gets really brilliant. And there’s not enough of that.

I read Juliet, Naked in two sittings and after finishing the first at page 154 I wasn’t sure if I liked the book. Then I read the second part and I loved it. That’s just a warning. Give it some time.

One review I read basically said that the book was okay, only Tucker wasn’t a very interesting character and why didn’t Nick Hornby try to be a bit more mysterious and twisty. I think that woman needs her head examined.

Lately I’m reading and hearing a lot of reviews that essentially demand that every book read like an episode of Lost. Now, twists are all good and fine in their right place. I’m sure crime fiction would be poorer if every novel told you who dunnit in the very first paragraph. (Some do, and are better for it. The attraction of rare things, I assume.) But the attraction in novels like Juliet, Naked doesn’t lie in the answer to the question of who will sleep with whom because of what. Novels like this one are beautiful because we get to examine the motivations behind what the characters do, in seeing their journey, their evolution. And that is made all the sweeter if you can see all the elements from the very start. This is not a flaw, Miss Myerson, it’s perfection.

No comments:

Post a Comment